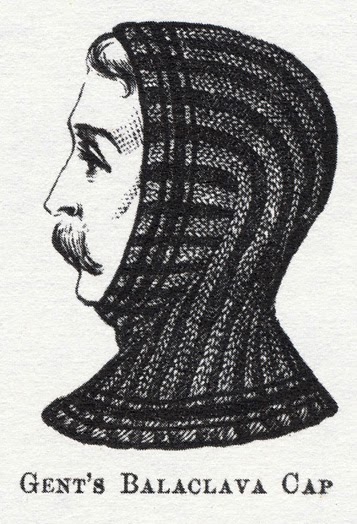

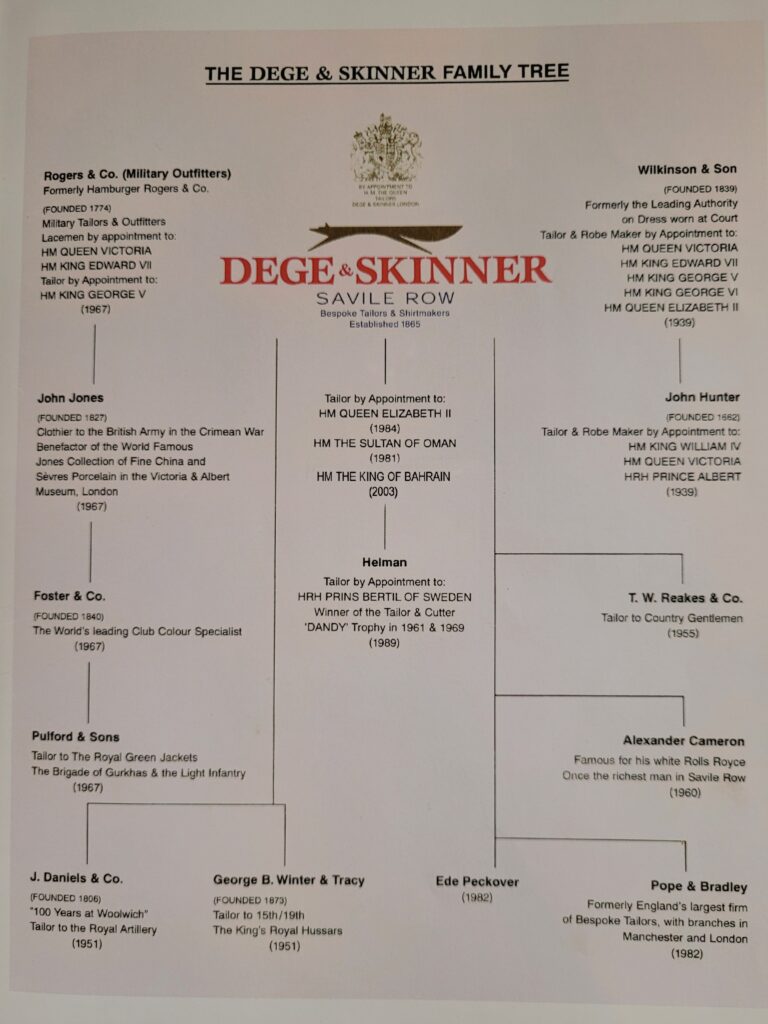

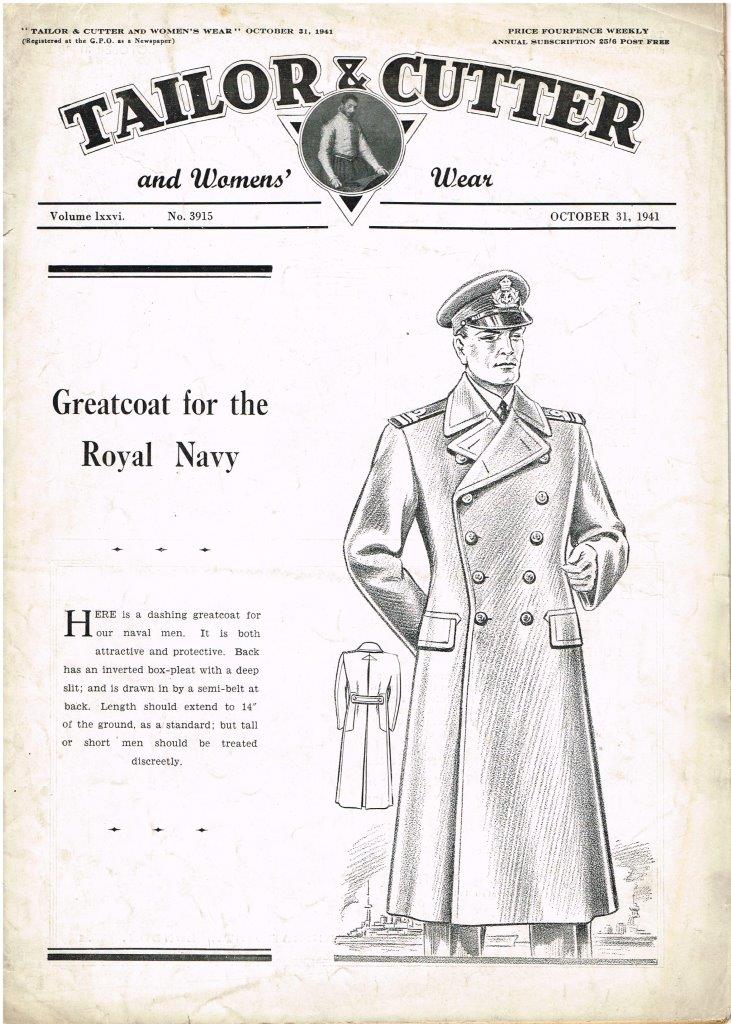

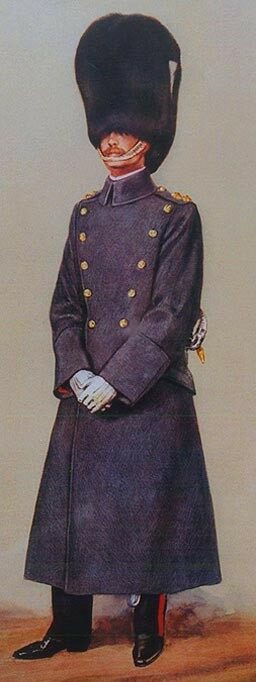

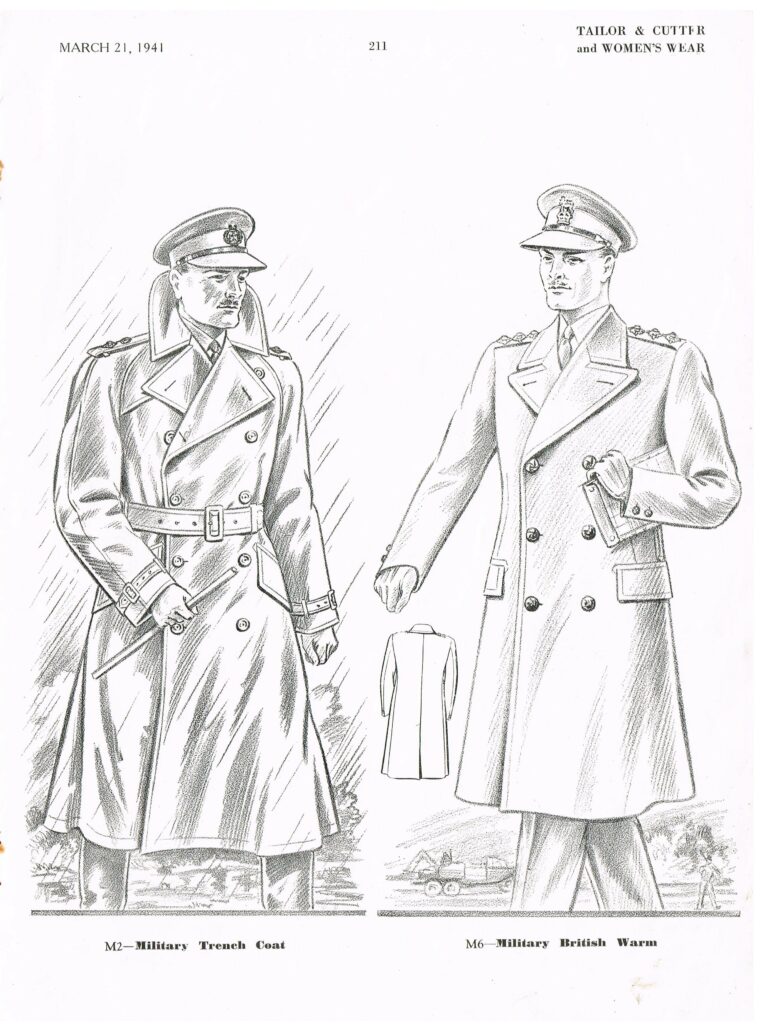

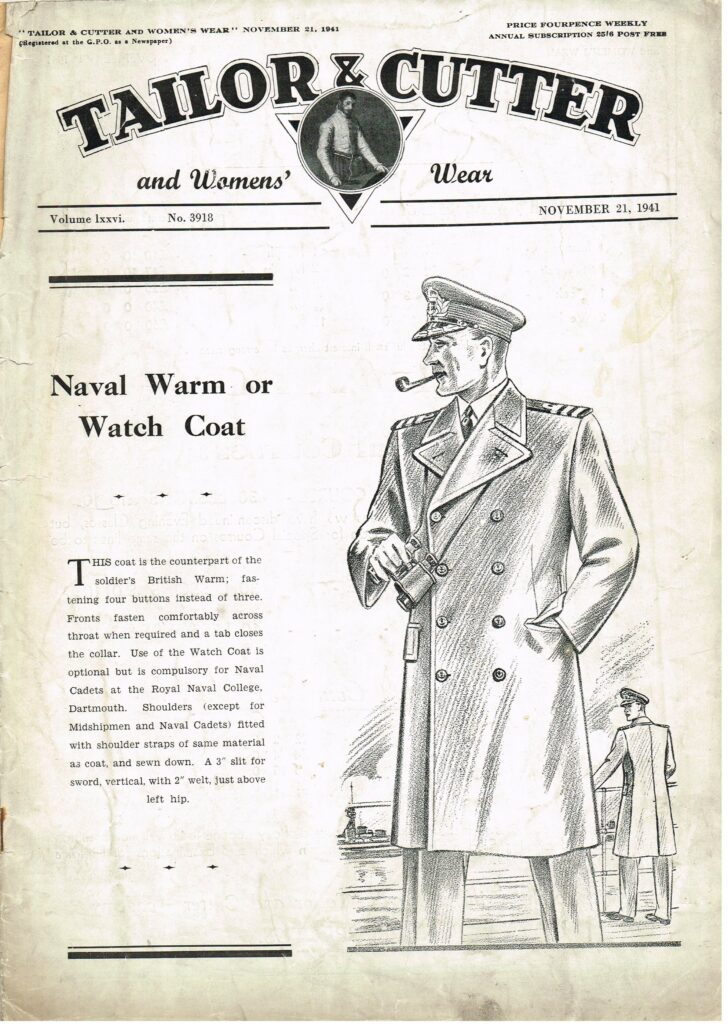

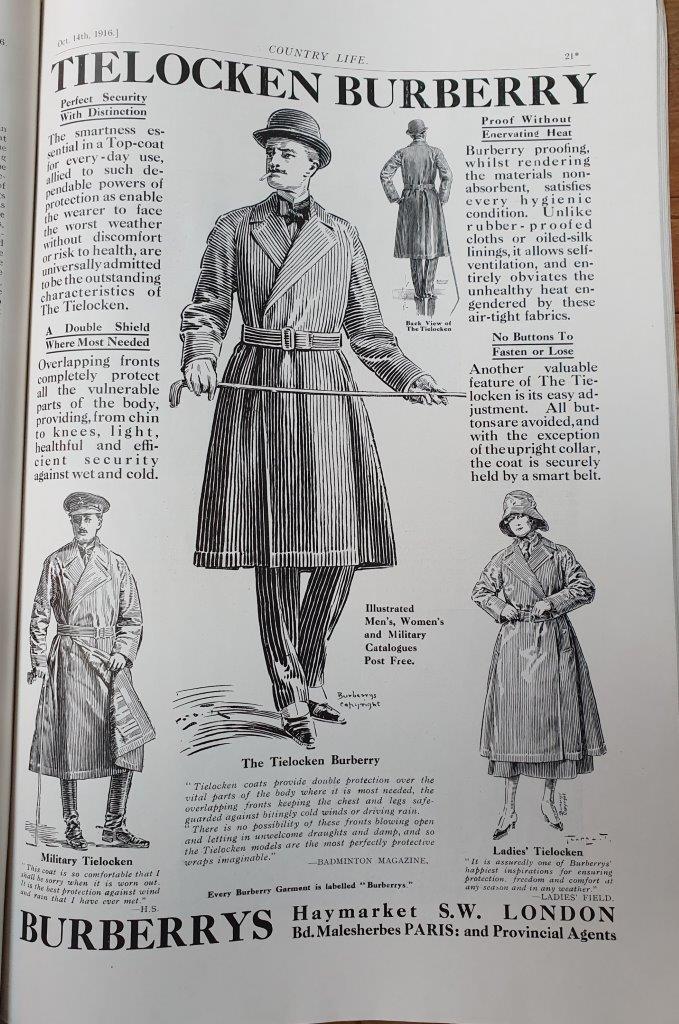

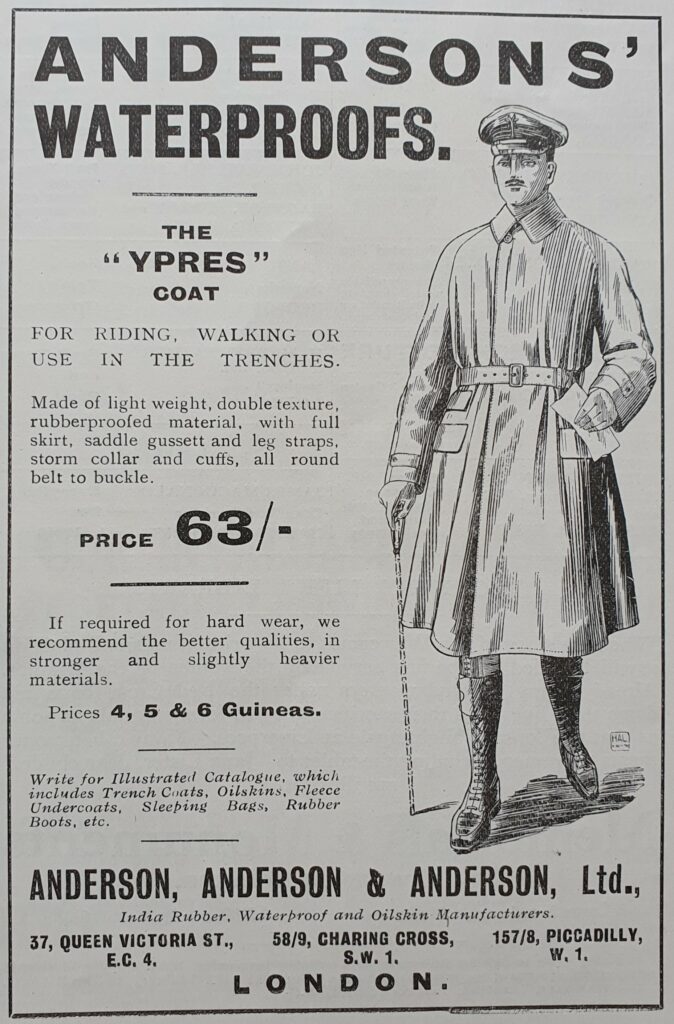

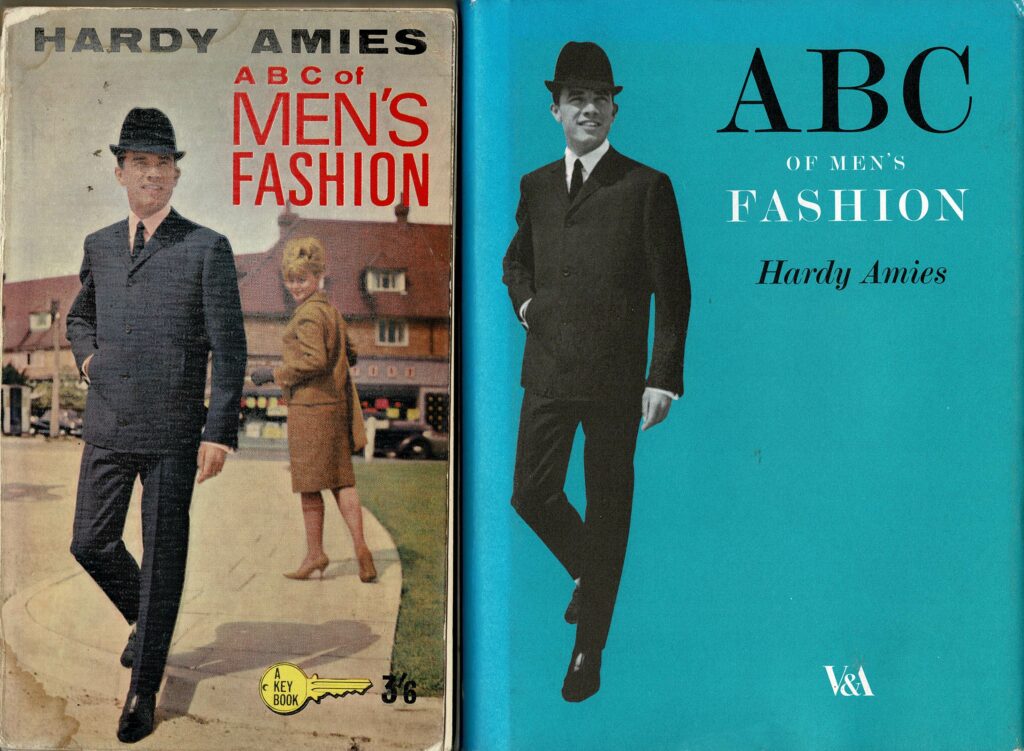

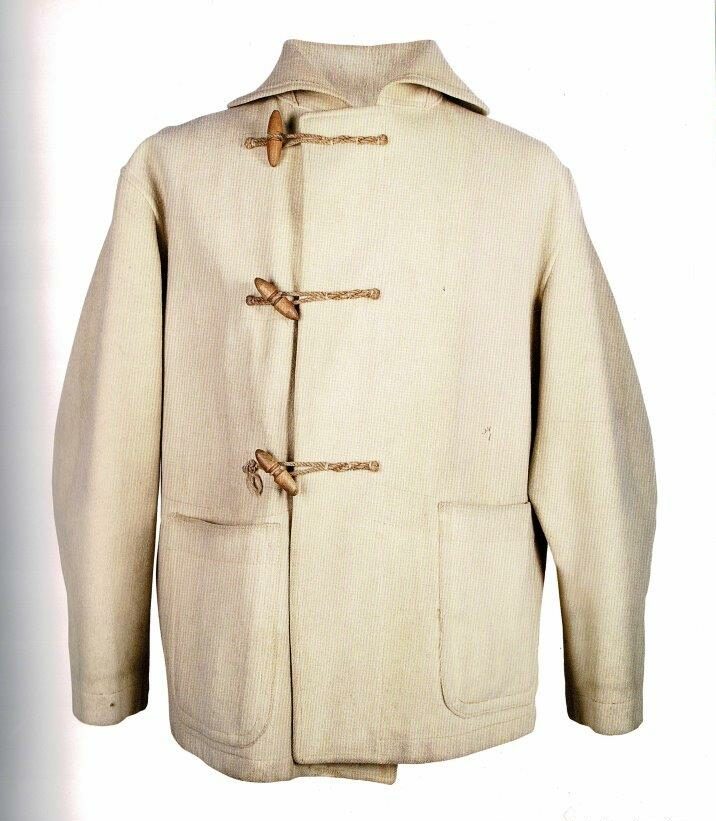

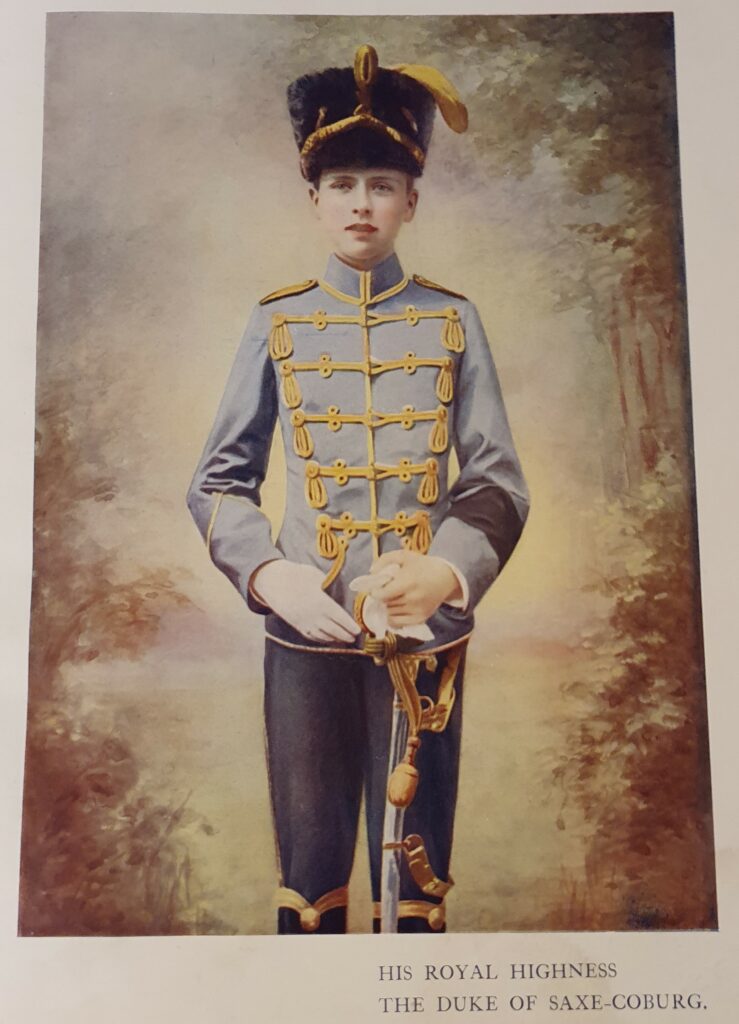

Some key elements of a gentleman’s wardrobe, especially for the winter months, have their roots in military and naval uniforms. It’s quite a legacy that brings with it several hundred years of fascinating history.

One of the purposes of clothing a body of fighting men in the same manner is to engender a sense of unity, of belonging and of correctness. These are precisely the same qualities that well-dressed men in civilian life, or Civvy Street to use a quaint old English expression, regard as important.